Unlocking PinkRabbit

tl;dr: I found some quirky software from the dotcom boom and restored it to working order. I'd love to tell you the story of how I got here if you stick around, but if you're more interested in a more direct description, you can head straight to the Internet Archive.

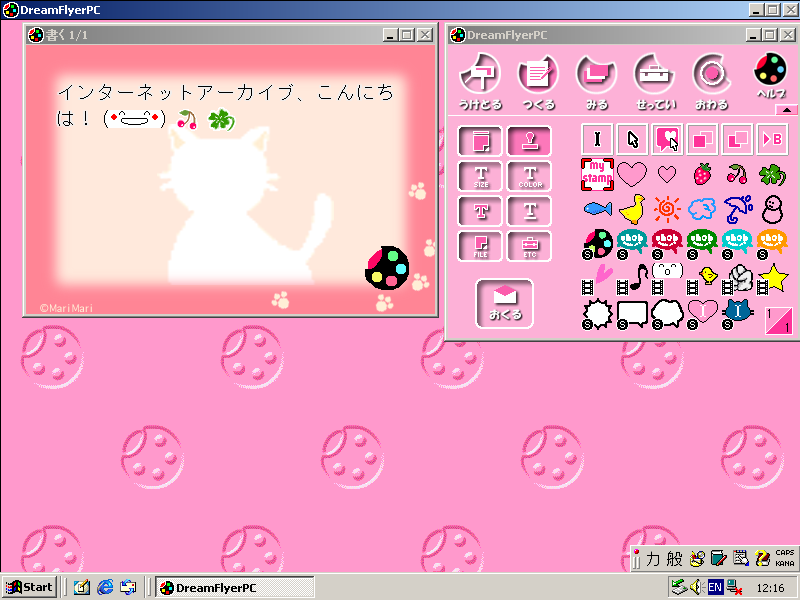

Part 1: Discovering DreamFlyer

Ever since I got a Dreamcast, I've wound up collecting some of the internet and multimedia software it was home to in its lifetime. I really enjoy the colourful and creative interfaces of its various web browsers1, and find the ambitions of their foray into downloadable content on 33.6kbps modems fascinating.

In 2019 I happened to be shopping for games on eBay and found a copy of DreamFlyer for US$1. I knew very little about it, and the internet seemed to know about as much2. Figuring it was something intriguing to add to the collection I picked it up.

I'd dabbled in getting my Dreamcast set up to send emails before, adapting Dreamcast Live's instructions to something that suited my email host and felt a bit better, running a mail relay on the DreamPi which would retrieve emails from a folder within my regular email hosting. It worked fine with Dreamcast web browsers' email clients, and it was fun to play around and discover that email has changed a lot in the past 20 years, but once DreamFlyer arrived I couldn't coax it into sending an email. I figured either it required a long-dead server, or just wasn't happy. I think I basically just forgot about DreamFlyer for a while.

For my birthday in 2021 a friend sent me a Sega-themed happy birthday, and my mind immediately went back to DreamFlyer. I decided I was going to reply with something composed in DreamFlyer. After all, even if emailing wouldn't be useful in 2021 I could screen capture it and send that. I spent a few minutes composing the flyer, covering it in all manner of stamps, took a screenshot and replied. And then I wondered, what if I tried emailing it again?

So I put in my own email address and hit send. I waited as it dialled up to my LAN, and then with a quick fanfare I got a message box. It didn't look like the error message I'd seen the last time. It had actually sent!

Jumping over to my phone, I refreshed my inbox, and sure enough, there was my email, with a "tml" attachment and this footer:

【添付データについて】

このメールはSEGA Dreamcastのメールソフト「DreamFlyer」で作成されています。●Windows95/98もしくはMacintoshをお使いの場合、以下のホームページから表示ソフト(無料)をダウンロードしてご覧ください。

http://www.dricas.com/dfhour/viewer/※お問い合わせ先:

株式会社セガ・エンタープライゼス

「Dreamcastサポートセンター」

電話:0120-258-254

Basically, it's saying that the attachment was composed using DreamFlyer, which is email software for the Dreamcast. Free viewer software for Windows and Macintosh is available from that URL, and if you need more information, you can contact SEGA Enterprises. Neat! I checked the attachment with a hex editor and it didn't have any recognisable format I could decipher3.

At this point I wanted to see my computer view the email, so I tried browsing that site. Naturally, it's no longer on the live web, so I turned to the Internet Archive's Wayback Machine. To my surprise, the executable had made it into a crawl. I managed to set it up in CrossOver with LC_ALL overridden to ja-JP. Cool! I fired it up, and was greeted with an error message complaining that the program had expired, and that I should download an updated version. Uh-oh!

Part 2: Unlocking DreamFlyer

This was a setback, but I fired up a VM with a copy of Ghidra. It's not the best, but it's the disassembler which has given me the best results for free so far. I spent a few hours tracing back from calls to GetLocalTime, but ultimately yeilded nothing clear-cut. I'd later learn that Ghidra didn't really know how to recognise any symbols in this binary.

Eventually I decided to try searching for string data, to see if I could find the strings related to the error message and work from there. I tried the strings utility, but the one provided with macOS doesn't have support for anything but ASCII text by default, and I was pretty sure I'd need Shift JIS support. Eventually I tried the same thing in Ghidra, and after scrolling through the list of strings, at the bottom I struck gold.

There, at 0x8a71a, was the UTF-16 string 2001/8/1. I checked the Readme, and indeed, it stated that the program would expire after July 31, 2001. Surely, I thought to myself, this was for informational purposes, or otherwise just a display string, but I edited it to a far-future date, fired up DreamFlyer, and it worked! I was able to view the email I had actually composed and sent from my Dreamcast.

At this point, I wondered about the Macintosh version the footer had mentioned - I have a lovely PowerBook G4 Titanium, and it'd be neat to send emails from the Dreamcast to it, so I scoured each revision of the DreamFlyer for PC site. Sadly, despite references to it on at least one page, I only managed to find that copy of the Windows version on ISAO.net, all the way until the site changed in 2001 to say it was no longer available.

That message, though, mentioned that users could move to a program called PinkRabbit, and import their messages from DreamFlyer, guiding users to move their "tml" files into PinkRabbit's "mailbox" folder. My curiosity was piqued, it looked like DreamFlyer was actually part of a much larger ecosystem! Indeed, peeking into the readme files supplied with DreamFlyer for PC revealed that PinkRabbit was an entire family of multimedia email software, including PinkRabbit-branded software for Windows and Macintosh, as well as FINAL FANTASY VIII Mail for Windows, Trihoo Mail for Windows, Kumomail for Windows and Macintosh, and several others.

With this discovered, I collated this information as well as copies of DreamFlyer's original installer and my patched executable, onto the Internet Archive.

Part 3: Tracking down PinkRabbit

With that put aside, I was intrigued by this broader family of applications. There was very little about it on the internet, and even scouring the Wayback Machine for any hints on their website came up empty.

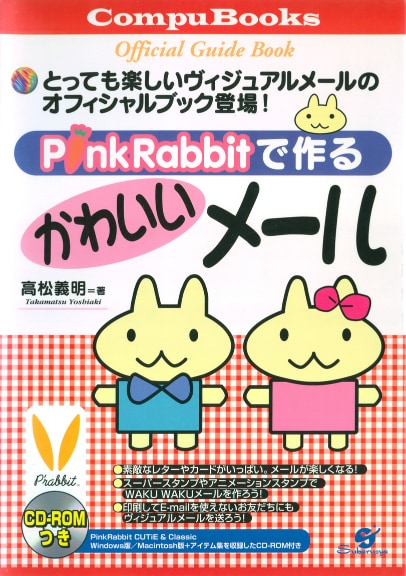

I tried searching more broadly for PinkRabbit, and after trimming down a lot of unrelated search result, stumbled upon the book 「PinkRabbitで作る かわいい メール」 ("Cute email made with PinkRabbit") by Takamatsu Yoshiaki (ISBN4-88399-064-8, published by Subarusya). This book originally came with a CD-ROM containing copies of two variants of PinkRabbit: Classic and CUTiE. My wife and I were already looking to import something from Japan, and I found a copy on Yahoo Auctions for ¥350. The listing wasn't clear on whether the CD-ROM was included, but for so little I thought I had to try it out. Bare minimum we'd get a decent quality scan of the cover onto the internet for the first time.

Further reading of PinkRabbit's website revealed that although the Macintosh version had not launched at the same time as the Windows version, it had been available since early 19994. This made the missing Macintosh version of DreamFlyer all the more curious given the Dreamcast version launched in December 1999.

Part 4: Unlocking PinkRabbit

It took a few weeks for the order to filter through local post and then out to international, but eventually I found the book in my hands. I gently flexed it experimentally, and it felt like there was a CD in there! Sure enough, flipping to the back page, there it was in all its pink glory.

I perused the book a bit with the help of some OCR translations. Along with a full colour section which gives screenshots of the included stationery and stamps, it revealed a little more about the original functionality. It was available for free via signing up for an online account, and had a companion online service which provided additional stamps, postage stamps and stationery for download. There was also the option to create your own sticker or stamp. Neat! Just like DreamFlyer, it had no vendor lock-in; you could point it at your own email servers just fine. The TransMediaLetter file format was the only proprietary bit of the chain.

Classic and CUTiE were also revealed to be two variants of the program, which didn't diverge that much at all; the difference coming down to the theming, graphics, and included stationery and stamps. Classic is a bit more neutral, but still pretty cute, while CUTiE goes all-in on the candy colouring.

Firing up a Windows 2000 machine with the Japanese locale installed, I popped in the CD. It AutoPlayed a web page, providing a choice of Classic or CUTiE, as well as a catalogue of the additional stationery included on the CD.

I got the program installed, fired it up, and was unsurprised to see the same expiry message as DreamFlyer. I wasn't sure if they would, but I guess it made sense that they'd have expiry on their own versions as well. With the knowledge I had from DreamFlyer it didn't take long for me to find a similar expiry date in the srabbit.exe executable, at 0x900fa. This limited use of this version to the end of 2003. I did the same as I had on DreamFlyer, opened it up again and... was greeted with the same expiry message! I checked and re-checked my work, tried changing the date in the other prabbit.exe executable, but no amount of fiddling with the dates got it working. Odd!

Looking at the supplied readme, I quickly learned that in addition to the quoted expiry date of the 31st of December 2003, it additionally included a 31-day trial timer.

使用期限はインストール後31日です。2003年12月31日以降はご使用になれません。

The suggested that the user could simply register for an account and download an updated version whenever that happened. Unfortunately, that registration system was long gone at this stage, and this requirement had all but guaranteed that no copies had survived.

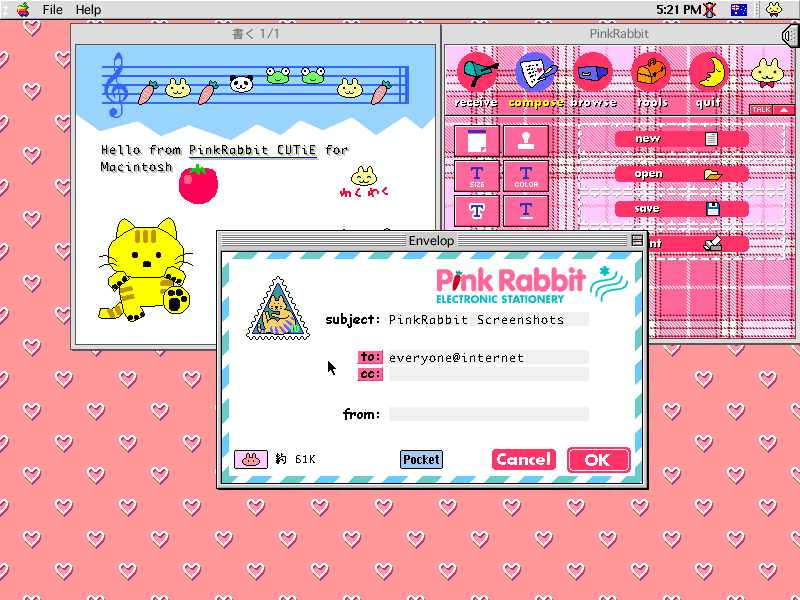

Well, that wasn't going to stop me completely. DreamFlyer already worked, and it was clearly very similar code, if not the same, so I'd come back later. I instead turned my attention to the Macintosh version. Firing up the CD on my PowerBook G4 Titanium revealed a pair of StuffIt Self-Extracting Archives for installers, and a similar HTML catalogue to the Windows version.

I got it installed, and fired it up. Sure enough, despite the Apple Platinum window borders, it had the same restrictions as the Windows version, and had long since expired. I discovered fairly quickly that the Macintosh version also had the expiry date within the application's data fork, this time as an ASCII string rather than UTF-16. Curiously, changing this string to a far-future date unlocked the application's functionality.

At this point I was a bit puzzled, and finding myself a bit out of my depth in reverse-engineering the Windows application, I put the call out online for help. In the meantime, I checked the other version, and it turned out that both variants had identical executables across both platforms, which would make it a bit simpler to patch!

Ninji was kind enough to answer the call. Sending my notes along with copies of the Windows installers, he set about reverse engineering the expiry error. Along the way we discovered some curiosities, like a mysterious debug mode activated by the mere presence of a debmode.ini file alongside the executable, which seemed to connect to a long-offline FTP server at ftp.gao.co.jp5.

It didn't take long for Ninji to find the routines responsible. It turned out to be storing a file in %WINDIR% called SRABBIT.001, and using the creation date of this file to control the expiry. Additionally, the code to handle this would add 32,400 seconds (or 9 hours) to the file's creation time in an apparent attempt to implement the Japanese Standard Time time zone. This instead meant that in other time zones the trial period on Windows wouldn't actually start for a few hours after installation. Sure enough, adjusting the creation time of the file by a few hours unlocked the application. Fantastic, waylaid on Windows by a late-90s time zone bug. 😂

Of course, this wasn't a permanent fix; the 31-day trial still applied, it just meant it could be worked around. Further investigation eventually revealed the routines responsible for this were retrieving information from another UTF-16 string in the executable6. This one was the string SRABBIT.001,31 at 0x90182. It turned out to indicate the file name, as well as the duration of the trial period in days.

Luckily for our purposes, the programmers had written a null check into this routine, meaning that changing this to represent an empty string (by changing the first byte to a null byte) stopped the program from creating or checking the creation date of the SRABBIT.001 file, and behaving like it wasn't a trial version at all! The Windows lockout was defeated!

With this knowledge I turned back to the Macintosh version, fired up Sherlock, and searched for "SRABBIT". Pretty soon I was pointed into the tmailbmp folder alongside the application. There was our trial control file. It seemed fairly likely that these were using the same code, then! I popped the application into HexEdit and found that SRABBIT.001,31 string was also present in the data fork, at 0xefd1f. Given the Macintosh's history as a Pascal-first system, this didn't appear to be a null-terminated string, which made me worry it might require more complicated patching. I also couldn't find a Pascal-style length indicator, and changing the byte before merely broke the executable, but it turned out that a null byte worked just fine! Both versions were unlocked. 🎉

Conclusion

With all that done, Misty submitted the PinkRabbit CD-ROM to Redump, and put a copy on the Internet Archive. I additionally contributed extracted and patched copies much like I had with DreamFlyer. And now both are there for anyone to play around with again.

It was a lot of fun digging into this artefact of the 90s where cuteness was the prime directive. I really wish more software was focused on being cute, computers would be a lot more interesting if they did.

Appendix: Novelties

Given the executables are the identical, PinkRabbit just looks for resource files in the directory it's stored in. This means if you were to copy the tmailbmp folder from DreamFlyer for Windows into PinkRabbit for Macintosh, PinkRabbit for Macintosh can become DreamFlyer for Macintosh! This makes the fact that Sega's variant seemingly never got its promised Macintosh release all the more puzzling.

While technologically divisible into those based on NetFront JV-Lite and those based on PlanetWeb, each region had its own spin on the formula, with Europe getting several editions of Dreamkey, North America a handful of Dreamcast Web Browser iterations. Japan got a bevy of iterations of Dream Passport, with various degrees of cuteness: Dream Passport 3 (my personal favourite), Hello Kitty Dream Passport, and Sakura Taisen Dream Passport. There's probably a whole other blog post in that stuff, though. 😅

Heck, Sega Retro still doesn't know much about it. I should fix that!

The Readme mentions copyrights of the Independent JPEG Group, but I couldn't find any conclusive markers of a JPEG image within the binary. I suspect they're either rolling their own container or obfuscating the contents. Also, minor spoiler warning if you jumped here from the referencing paragraph, but I got it working and the image looks very much to be JPEG compressed.

What a cute web page to introduce the Macintosh version! Someone over at COLABO clearly cared. There were even skins released to match DreamFlyer with the colour of your iMac's case!

I haven't worked out what this was doing, but I might have to fire up an FTP server and see what it looks up someday. Perhaps they had beta/debug builds distributed this way?

These later turned out to be Windows string resources, and I regret not getting out Resource Hacker earlier in the piece 🥲